49. Peculiar

You know what they say about assumptions.

I had assumptions. I admit it. I did.

A few months ago, I put off responding to a request to give a speech to the Sunstone Symposium for weeks, torn about what to do with such an invitation. Why would a conference about Mormonism want me as a speaker? What could I possibly say that they didn’t already know? Time, and age, and the nature of my work, makes me suspicious by nature, and I wondered if this was a complicated ruse by angry Mormons who wanted to chastise me for writing a book about a religion of which I’ve never been a member.

But, because I hate nothing more than when people make assumptions about me, I eventually replied, yes, sure, I’ll come to Utah, and then for months I sat in front of a blank screen and a blinking cursor as I tried to figure out what to say.

The Sunstone Symposium is a conference put on by the nonprofit magazine of the same name — a publication that, throughout its 50-year history, has been consistently controversial because of its openness to ideas frowned upon by the leadership of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and wider Mormon culture. Sunstone is a place for current Mormons and ex-Mormons from across a wide spectrum to convene: Mormon feminists1, Mormon historians, queer Mormons2, progressive Mormons, even a host of people from polygamous breakaway groups. Sunstone’s motto is “more than one way to Mormon.” The few people I met this weekend who actually remain members of the LDS church were in attendance because it’s a place that nurtures free thought and expression, faith free of boundaries.

I gave the speech, people asked smart questions. No tomatoes were thrown.

That speech was really a footnote for me, though, because afterward I got to attend the conference for two days. And let me hit you with this disorienting reality: I traveled to one of the most conservative states in the country, to a conference centered on Mormonism, and witnessed some of the most productive discussions I’ve experienced about (1) the oppression inflicted by patriarchal systems, (2) the nature of truth and (3) how to go about the work of decolonization. Example A of why journalists should never paint an entire group of people with a broad brush, and neither should you.

I learned about the history of drag in Utah. I meditated at a session led by a Mormon witch. I heard polygamous women discuss their beliefs that females should have priesthood powers. I heard people nerd out on new levels about LDS history.

I started to hear a common theme emerge as I floated from room to room— that anyone within the broader Mormon milieu cannot truly tell an accurate story of the faith and their ancestors without also discussing the blood of Indigenous people on their ancestors’ hands, the colonialism baked into the faith, and how the patriarchy of church nests inside the patriarchy of American society. The concepts these discussions led to might inspire future newsletters here; there are no clean answers. But my takeaways were that these discussions were wildly productive and centered on caring for others, instead of pushing people away. They’re discussions that could be had by most Americans — not just Mormons.

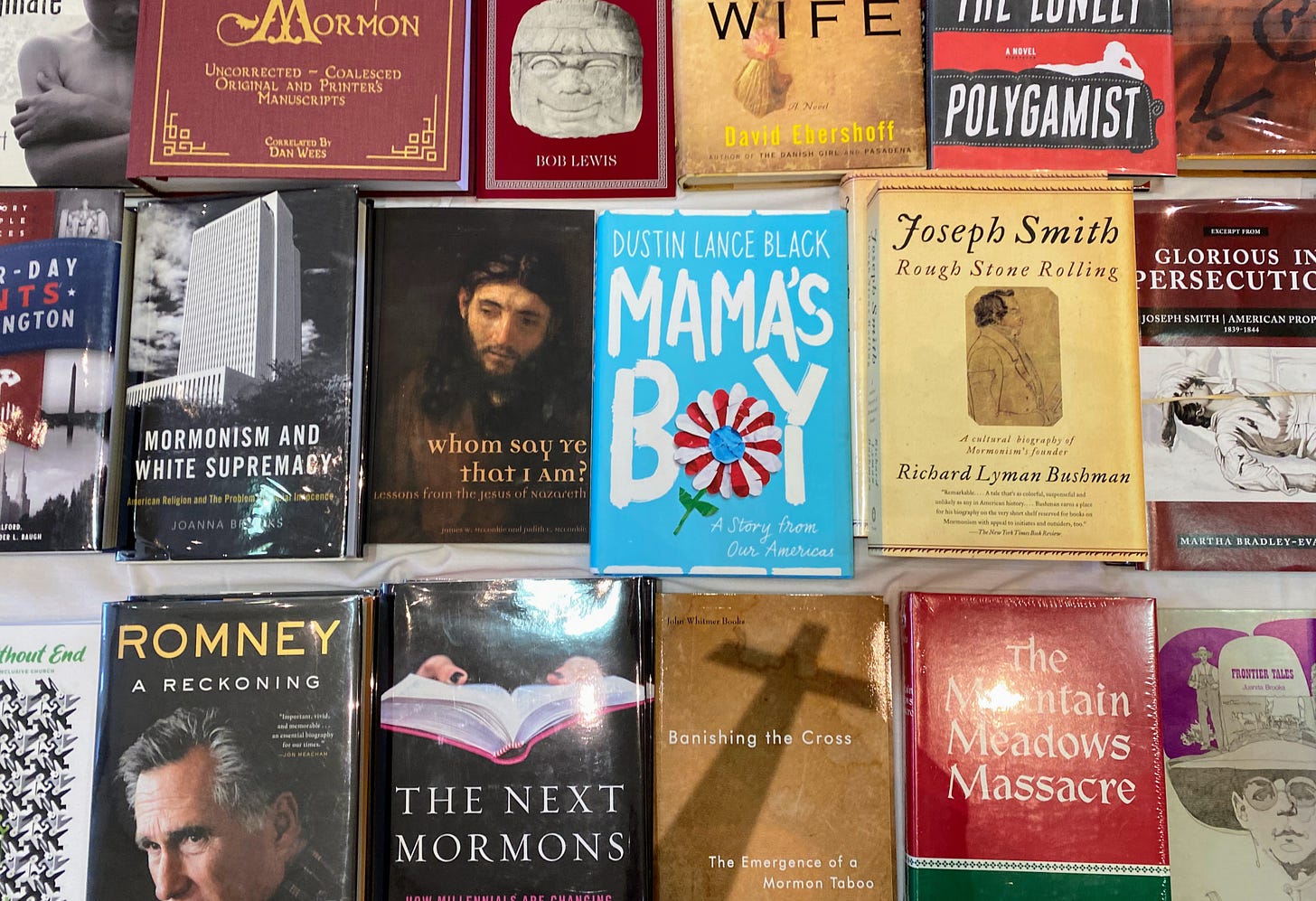

One day, in between sessions, I was shooting the shit with the fine folks at Benchmark Books (who generously hosted a signing of When the Moon Turns to Blood) about a copy of Harold Schindler’s 1966 book Man of God/Son of Thunder on Orrin Porter Rockwell when I overheard a conversation by a couple of my fellow book browsers. They were talking about the nature of truth, and the caveat that runs at the beginning of Fargo.

If you’ve seen the Coen Brothers movie, or the spinoff television show, it starts with a note that “This is a true story.” But … it’s a joke — one, I admit, I’ve never understood. Fargo is fiction. But the point here is that what I could deduce from eavesdropping on these fellow Sunstoners was that Mormonism could come with a similar kind of caveat. Church leaders say “this history we tell you is true,” when in reality it is very often the opposite.

And what is “true” anyway? True for me is different than true for you. But, more pointedly, what is a fact? And how do people who want to know the raw, unadulterated reality of the past reclaim facts from the powerful actors who’ve manipulated them? Again, these are questions I think all people could be asking. And Sunstone shows how difficult reclaiming truth continues to be for Mormons: so many individuals, in a search for truth, simply have claimed access to new truths. Then comes the conspiracy-mongering. The revisionist history. The power shifts from the First Presidency of the LDS Church to some guy on the Internet who says he receives revelations. Breakaway groups use their new versions of truth to further subjugate people. It gets messy. People are messy.

At the end of the conference, on Saturday evening, a vast majority of attendees gathered at a park underneath a picnic shelter as the sky darkened, clouds rolling in. There were taco fixings and trays of churros and coolers of soda (caffeinated, even!), and everyone listened as a trio of people from the queer community got up and told the audience their stories. The wind blew sideways in mean gusts, scattering foil trays of shredded lettuce and tortilla chips. The lights of the shelter never came on as an evening storm set in; people stayed nonetheless, listening in the dark.

The speakers confessed their fears of rejection if they came out, told stories of lost faith, lost hope, lost family. Even the most fundamentalist polygamist attendees — ever-present in their suit vests and button-down shirts — kept listening to the stories.

The sun became a memory. People became silhouettes. My eyes strayed to the horizon as the stories went on, where the last bits of day remained. It is a privilege to watch a storm roll over the Wasatch Front: dark clouds rushing like a team of horses galloping toward battle. I couldn’t help connect that image to what I was hearing: person after person who refused to deny the truth of who they were, despite so much pressure from the church. To deny who you are is impossible, like trying to negotiate with a thunderstorm. Both carry a crushing inevitability. There is inertia to who we are inside. Our identities are like weather.3

Despite my years of reporting on Mormonism, this weekend I heard a recurring term that was new to me: that many Mormons consider themselves “a peculiar people.” People said that again and again. “We are a peculiar people.” And as the stories continued that night, the comfort of that peculiarity set in. Here were people who, by the nature of the faith in which they were raised, feel like outcasts of American society. And then from that group of outcasts, these individuals had pushed themselves away even further — by leaving the church, by leaving faith behind completely. And now they convene: peculiar outcasts of peculiar outcasts. Drawn together like magnets instead of being pushed apart. They talked past day, into night, proudly peculiar because they aren’t standing alone.

If you missed my announcement last month, I have a new book coming out in March 2025. It’s called Blazing Eye Sees All: Love Has Won, False Prophets and the Fever Dream of the American New Age. I can’t wait to talk about this wild project I’ve been working on for years. Email me if you’re a bookstore who wants to host an event!

You can pre-order the book now from the bookstore of your choice here.

It’s a long time away, I realize, but pre-orders have a huge effect on the overall success of a book in the long run. So if you buy it now, not only are you gifting yourself a book in the future, you’re really helping this eternally-toiling artist out, too.

The LDS Church has a controversial stance on feminism; in 2020, The Salt Lake Tribune unpacked the leaders’ messaging further, a piece that included a crushing line about how the dreaded f-word is a label that can be used by church leaders to “dismiss fellow saints who have different political and cultural viewpoints.”

I was reminded during this story-telling event of a piece I wrote in 2019 for the now-shuttered California Sunday Magazine about a former Mormon conversion therapist named David Matheson who had, by then, come out as gay. During this story, I watched as Matheson had a tense conversation with a former patient about the trauma he carried from that conversion therapy — a truly stunning, sobering and heartening conversation to witness. You can read some of that here.

Beautiful! I'm glad you went. Part of the reason I like your writing and podcasts is that you are so respectful of people who have wildly different backgrounds and points of view from your own, while still calling out horrific stuff. As I get older, the more important I think it is to be open-minded. So important. I've come a long way. Still have a ways to go, I imagine!

Thank you so much for the wonderful and informative story. I can't express the sheer joy your writing brings to me and many others. Thank you.