I learned people hate the media during my first few months as a rural reporter at a small-town newspaper.

Sometimes people did not want to talk when I called because they believed I would distort the truth or manipulate their stories for my own amusement. I admit that felt a little silly; usually I was calling about the opening of their hair salon or daycare center.

This idea that reporters can’t be trusted, that the media has its own agenda surprised me: I’d been fed a story in journalism school that we reporters were holding up democracy by informing the public. Writing about a hair salon was a very tiny piece of that. On the job, though, it was clear to me that everyone did not share that same rosy view.

In my case, it quickly became clear why people didn’t trust the little community newspaper where I worked. Reporters were a dime a dozen. Mine was a low-paid first job a string of recent grads before me and after me took to learn before they moved onto the next thing. Trust takes time and effort to build, and that’s hard to get when you are just the latest person using a community like a classroom to learn. As it was, I was only in the job for six months before I moved on.

Over time I learned the value and the precious nature of earning trust. One way I learned to gain trust was to ask people what other reporters got wrong about their story. I continue to use this tool all the time: “tell me what everyone else got wrong. Tell me what you think people misunderstand about you. We’ll start our conversation there.” This doesn’t make me sympathetic to their story, but it does give me a baseline to work from. A way to feel out their sensitivities.

This is one benefit of my otherwise benefit-less role as a weird freelancer: usually I’m the last person to arrive to a story. I take my time. Sometimes I’m calling people years after other media have moved on, after tempers have cooled and perspectives have been gained. Sometimes that tension over what everyone else got wrong — becomes a part of the story I write.

For a long time, I clung to the idea that the media, writ large, was misunderstood, misrepresented. After all, this is a profession that, like doctors, comes with a code of ethics. But I think most of the general public’s perception of reporters comes to them through movies and television.1 We are a culture obsessed with achievement and celebrity, and so perceptions are created by the reporters people perceive to be at the top of the proverbial pile, the heads talking on CNN, Fox, MSNBC. I would venture a guess that the local and regional journalists who slog away for bullshit paychecks to inform people in the very communities they live in don’t come to mind when most people picture a journalist in their head.

But I’m experiencing a personal shift. At this point, I would be sticking my head in the sand if I blindly trusted the media, too. In fact, I get a sour taste in my mouth when I think of myself as being a part of an industry that, more and more, I find myself at ethical odds with. One day this week I opened up the news in the morning and all I saw were stories of fear and murder and politics. Then, later that day I was researching a story and pulled up a paper from the 1970s. It, too, was all fear and murder and politics. Nothing has changed. Maybe I’m the one changing.

Journalism is built on a set of rules and practices that are about as solid as a waterbed. Objectivity is in the eye of the beholder. In the process of making something widely readable, complicated truths are distilled down by a writer. But there is a very fine line between distillation and distortion.

Facts are gathered, but it doesn’t mean a journalist will use them all in their story. At worst, a journalist may set up facts like cones in an obstacle course and figure out how to navigate around them to tell the story they want to tell. That their editors want to tell. That their readers want to click on.2

Media heroizes itself with an altruistic story of truth and justice and public service. And some outlets are absolutely achieving and working toward those goals. But too often, coverage only serves certain audiences. To go far in journalism, you are likely white, wealthy and well-educated. But how can you build trust if you’re only writing about a certain subset of society? And why would anyone trust you if your reporters don’t represent a diversity of backgrounds and life paths?

Here’s a great example. My good friend B. Toastie Oaster writes in High Country News this month about the tensions they feel balancing their Indigenous identity and their role as a reporter when writing about sacred places. An excerpt:

I want the public to understand the importance of these places, and part of me wants to tell my editors everything. But if I do, and the information escapes, it will be on me. I’m Native, too, and I have to handle this information responsibly, without selling out my kin. In the Native world, we tend to view each other — and all living things — as relatives. At the same time, my tribe is not from here, and I’m still learning about the cultures I’m reporting on. Language that would bring the location vibrantly to life is right there in my mind, but I don’t feel right about using it. The most I seem to be able to tell my editors — speaking accurately and honestly while respecting cultural concerns — is that tribal leaders won’t share that information with me

Oaster is a rarity - a person who understands the ways media has caused harm and can continue to. (High Country News, too, is a rarity.)

Too often, instead of holding power to account, media cozies up close to it and punches down at vulnerable communities. It suckles at the teat of the powerful by mimicking their talking points. Journalism’s twin obsessions are winning fancy awards and scooping other media outlets — things that only matter to journalists, and rarely register on the radar of readers.

Trust gets cast aside.

After a strange month in journalism, I’m at my desk offering you this missive, this lament, as I try to understand where I fit in this industry — an industry that is beyond broken. I truly believe in the practice of journalism, but the people making it thoughtfully and ethically get drowned out.

A few weeks back the newsletter Status reported that New York Magazine’s DC correspondent, Olivia Nuzzi, engaged in a “personal relationship” with former presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. — a person she had profiled for the magazine. This spawned a million follow-up pieces about a reporter sexting a source and the nature of journalists’ relationships with their subjects.3

Moira Donegan wrote what I view as one of the more clear-eyed views of this tawdry affair for The Guardian about how the Nuzzi/RFK effect will be felt the most by female-identifying journalists. An excerpt:

The most ungenerous interpretation of Nuzzi’s career – which is not necessarily the most likely one – is that she used her youth and good looks to her advantage, flattering the egos of men who could get her jobs or serve as sources. In this scenario, she would have made a trade-off – sexual attention for professional opportunity. There is a tendency to demonize this kind of use of sexuality by women (and a less pronounced, usually tardy tendency to criticize such trades when they are demanded or accepted by men). It is this tendency, feeding off the unspoken and unproven assumptions about just what Nuzzi and RFK Jr were offering each other, that has led to all the slut-shaming of Nuzzi in the media.

Women who make such trades are not necessarily unequipped for the jobs they get by them: talent and corruption often coexist in one person. (And whatever the controversies and uncertainties about Nuzzi herself, there is no dispute that she is very talented.) But the problem with such transactions, where they do happen, is not that the women who make them are sluts. It is that they are scabs. Such trade-offs can be consensual, but they can never really be ethical: they make it harder for other women in their industries who are not willing or able to use their sexuality to advance to do so; they set the precedent that sex for opportunity is an acceptable trade to make to female workers; they encourage men to leverage their professional power to extract sexual favors. They cast all female professionals under the suspicion of corruptibility and unseriousness.

The last two weeks of September were all Nuzzi Nuzzi Nuzzi. I couldn’t stop reading about this ordeal, finding every aspect of it unrecognizable. “This,” I kept thinking, “is what people think journalism is.” Sex and power. Not trust. Then I’d turn back to the pile of public records I need to read through, drink my third cup of coffee and realize - shit - it’s 2 pm and I’m still at my desk in pajamas. So much sex, so much power.

I’ve been in this industry long enough to know that Nuzzi will keep her job or get a better one. Look at the people who’ve come before her who’ve broken ethical standards, but kept their jobs. People tend to fail up and up and up in journalism, even when they make egregious violations of trust. Ethics and hard work are not necessarily rewarded in legacy media.

More big media news came this week, this time about something much more positive, more groundbreaking. The reporter Taylor Lorenz — whose work on the Internet I admire — announced she’s jumping out of the plane of legacy media, and going full-time on her newsletter, User Mag.

There’s a great piece on her move in The New Yorker. An excerpt:

In 2024, Lorenz told me, she no longer sees a reason to remain associated with the mainstream media. “I don’t need it for credibility,” she said. “I don’t need it to reach an audience. I don’t know what it does other than connote prestige for a shrinking amount of people.” She added, leaning into exactly the sort of rivalrous drama that plays well online, “Legacy media sucks, it’s crumbling, and, by the way, I’m going to dance on the graves of a lot of these places. … I don’t want to be a full-time writer. I want to be an Internet personality.”

I’ve always appreciated Lorenz for her honesty and how she somehow got the stuffy world of journalism to allow her to report for a new generation of readers. She treated the Internet seriously because, as The New Yorker points out, she’s a denizen of it.

She’s certainly not the first person to say bye-bye to legacy media in favor of a newsletter. But something about the way Lorenz framed her reason for going gave me the reminder I needed that for me to continue making journalism, I have to remain insistent on doing it my way. I do that for working for publications and organizations (namely Oregon Public Broadcasting and the aforementioned HCN) whose ethics I can stand behind, places who prize trust and creativity, who take time to get things right.

Lorenz can afford to dance on the grave of legacy media because, as she said, she aspires not to be a writer, but an Internet personality.

I am a writer and I have no interest in being an Internet personality. To be a personality is to have a desire to perform, and that’s not what I’m doing here. I want you to know me only through my words. I’m trying to give it to you straight. I’m trying to do right by my fellow humans. I don’t want a ring light and perfect makeup to be a requirement of my craft.

The only thing I need is trust.

Speaking of trust, this week I got to see Jesse Lee Johnson in person for the first time in a year. It took Ryan Haas and I about five years to get people on Johnson’s legal team to trust the idea we had to make a podcast about his 26 years living on Oregon’s death row. (If you haven’t started listening to Hush yet, that’s not a spoiler, by the way, that he’s out.) His life story is absolutely fascinating.

Johnson took the stage at Portland’s Soho House, of all places, where the Oregon Innocence Project brought him into town as a guest. On the stage, he thrust his fists in the air and said he always knew he would get out of prison. He broke down crying, thanking the people in that room for working tirelessly to free him. It was quite a moment.

Just a couple more things and then I’ll leave you alone:

A ZOOM EVENT: Last month I asked folks here if they’re interested in a workshop about how to obtain public records. I’ll be hosting that workshop on Thursday, October 24 at 6 pm Pacific via Zoom, joined by my reporting partner on Hush and fellow records nerd Ryan Haas. We will run you through some of our tips and strategies for obtaining records, then take your questions. Sign up for that workshop here! The point of signing up is so I can send you the link, but also to cater our presentation to your interests.

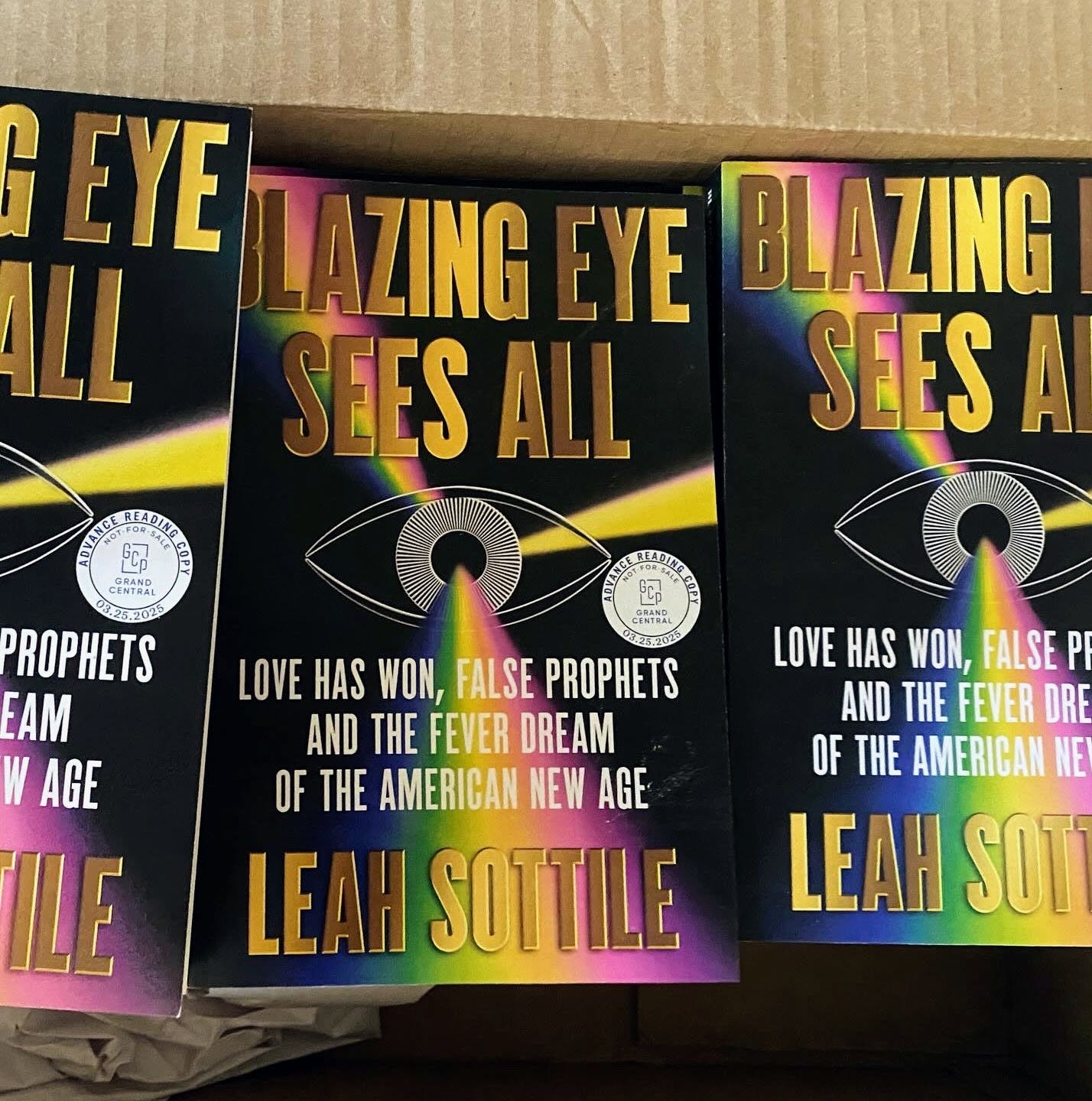

BOOK FORTHCOMING: A couple weeks ago I received a box of galleys of my forthcoming book Blazing Eye Sees All. Ain’t she a beaut? As I’ve mentioned, the success of a book can be determined by preorders so please consider ordering the book now. You will be so happy when a little gift shows up in your mailbox in March.

ON THE ROAD: On that note, please comment below if you’d like me to make a stop at a bookstore in your neck of the woods. Suggestions appreciated!

I’ve written a bit about this before, but sometimes I think people don’t even believe journalists still exist. We do, I swear.

I hate to waste any more breath on it, but a great example of this is the story the national news put out this week about how Portland is dismantling its local government (it’s not) — a piece that eschews doing any new reporting, leaning on old statistics about gun violence and ignoring the fact that the police budget is larger than it has ever been in history. Go find it if you must, but if you do, you must immediately atone by becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter.

If you’re going to read anything about the whole ordeal, I recommend Lachlan Cartwright’s piece for Vanity Fair. Conversely, if you would like to throw up in your mouth, read the disgusting perspective of former New York Times media reporter Ben Smith.

Thank you for saying it! The idea of needing to become an internet personality to survive in journalism and writing makes me want to do just about anything else. I think the industry shifting responsibility for its traffic on writers' online personas has led us to a dead end.

“I am a writer and I have no interest in being an Internet personality. To be a personality is to have a desire to perform, and that’s not what I’m doing here. I want you to know me only through my words. I’m trying to give it to you straight. I’m trying to do right by my fellow humans. I don’t want a ring light and perfect makeup to be a requirement of my craft.”

Whew, yes.