It is November 19 20 21 22 when I am writing this, and since November 5 I have felt profound pressure to say something. Say something my inner voice is pestering me. You must have something to say.

And yet … I don’t have much to say. For years, I’ve been saying a lot. I am out of words. I can say what I see, which is what you also see: the United States elected a convicted felon and sex abuser and proud authoritarian as President. The electorate turned a cold eye on women and the queer community and people of color and immigrants and basically anyone who is not white and/or rich. Were they tempted by outright racism, intrigued by bigotry, fooled by empty promises of economic prosperity and a gilded, glittering white future? Surely. Michael J. Socolaw had a great way to put it in the week after the election:

“It’s likely that women who have been sexually assaulted voted for him, knowing he’s sexually assaulted women. Business owners who pay their taxes and abide by legal and regulatory filings know that Trump has evaded both obligations — and still voted for him. Military servicemen and servicewomen who know what Trump has said about their dead predecessors and heroes such as John McCain still voted for him.

Millions of well-informed, moral, ethical, and law-abiding Americans who know all about Trump’s behaviors, malfeasance, and illegalities, and his threat to democracy and constitutionality, voted for him. Somehow, despite reading and absorbing verified truths and accurate reports about Trump, their voting behavior failed to match their knowledge. That’s not the fault of the news media. They did their job.”

I read Socolaw’s piece and felt seen. It made me think of all the times someone made a quip about my work not being nice. I really do get that a lot: that my work is hard to read, difficult, uncomfortable. Which, okay, I get it. No one is making you look at hard things. And yet, I can’t imagine how tough these past two weeks have been for those who haven’t been actively forcing themselves to understand what’s happening around them, who are now looking directly into the eyes of a very difficult future.

I’m exhausted. The day after the election, I got COVID for the first time. First time! Not over-rated, turns out. It made me very fucking sick. Then, in a freak accident, my partner Joe partially amputated a finger. Lotta blood. Then our van broke down. Did I tell you our dog died? And then, and then, and then. Our life feels like a comedy at this point, and the election is the noise behind it all. A screeching soundtrack composed by maniacs.

I’m driving to the mechanic, RFK is announced on the radio as someone who will now “make America healthy again.” In the emergency room, Joe is deep breathing and social media is telling me an accused sex offender is being put up for Attorney General. The blood soaked bandage is easier to look at. I’m focusing on what’s in front of me. Driving to the doctor today, Joe gets a call: we’re laying you off from your job. (See the conveniently placed button below because, hi, in case I haven’t been clear, freelance journalism does not pay the bills.)

The waves of terrible are not coming in threes. They are coming in dozens. They are an ocean.

After the election, liberal people on my social media feeds were talking about learning to shoot guns. I thought about Chekhov and his gun — the literary concept that if you, as a writer, introduce a gun into the plot of a movie, a book, a play, that gun will need to be fired. Ask yourself: who are you going to shoot with that gun? Because, now we know, that all around you are people who likely voted for Donald Trump. Are all of them now your enemy?

Ask yourself: what part will you play in this drama, this tragedy? Will you indulge in conspiracy theories that the election was stolen? Will you be an Ashli Babbitt?1 Storming the Capitol because you believe Trump is Q? Will you be Lavoy Finicum?

Who are you, really? Have you asked yourself that? Have you thought long and hard about what you are willing to stand up for? Will you, as Timothy Snyder says, obey in advance?

“Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.”

Can you let yourself consider that, perhaps, fighting is an integral part of living?

After the election, in a feverish COVID haze, when watching TV and playing video games started to make me feel stupid, I pulled a book off the shelf I’ve been waiting for the right time to read. It’s called The Stranger Next Door: The Story of a Small Community’s Battle Over Sex, Faith and Civil Rights. It was published in 2001 by Arlene Stein, now a sociology professor at Rutgers. It woke me up.

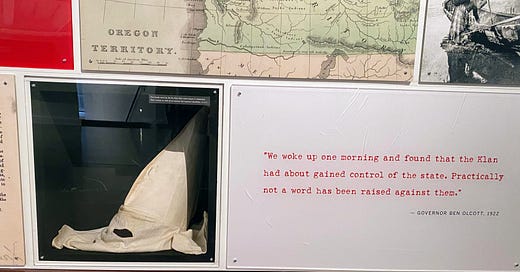

Stein was drawn to Cottage Grove, Oregon2 to document “how a small community with a declining industrial economy became the site of a bitter battle over gay rights. Fearing job loss and a feeling of being left behind, one Oregon town’s working-class residents allied with religious conservatives to deny the civil liberties of queer men and women.” What drew her attention was Measure 9, a 1992 citizen’s initiative that was, without parsing my words here, steeped in bigotry.

Measure 9 was a sharp tool fashioned by the far-right intended to “amend the Oregon Constitution” in order to “prohibit government promotion, encouragement or facilitation of homosexuality, pedophilia, sadism and masochism,” among other things. It was the work of the Oregon Citizens Alliance (OCA), a “conservative activist group,” which devoted itself to undoing protections that prevented the discrimination of the queer community.

“The effect of this measure is to establish the right of citizens to challenge governmental promotion, encouragement or facilitation of homosexuality, pedophilia, sadism and masochism,” it read.

Measure 9 failed by a thin margin statewide. And it was hardly the end of the OCA. The group turned around and began sponsoring local initiatives to prevent cities from “spending to promote homosexuality.” It was on this front the OCA found great success.

Across Oregon, OCA’s bigoted local measures were embraced by voters in Springfield and Cornelius and Canby and Junction City and Estacada and Lebanon and Medford and Molalla and Sweet Home and Keizer and Oregon City and Albany and Oakridge and Roseburg and Veneta. In Lake County and Klamath County and Josephine County and Linn County and Jackson County and Marion County. 3

You see what I’m saying here? History repeats. Why does anyone think it won’t? Hatred and bigotry have been embraced before. Look at Measure 9.

As I read her book, I became more gripped by the fact that this reality has always been in front of our faces.

I sent Stein a fan email. I asked her, “do you feel like Cassandra?” Warning of us of impending doom while the world keeps moving regardless?

We got on Zoom to talk.

“I wouldn't say that I'm a Cassandra,” she said, “but what I'm writing about in this book is about the rise of right-wing populism and the ways in which the right is at least partly organized to divide communities. And to divide communities by creating an ‘us’ and a ‘them.’”

Stein came to Oregon to work at the University of Oregon in the sociology department, and planned to study a number of small towns that were gripped by Ballot Measure 9. She honed in on Cottage Grove for her book, where local OCA efforts were spearheaded by a “little housewives group,” she told a group during a Rural Organizing Project event in 2023. “Female OCA activists saw themselves fighting for their families.”

“I do think they were motivated by the belief that traditional values,” Stein said, “and a lack of tolerance for homosexuality was something that would make this community and country stronger. That we had gotten too far away from the values that made America ‘great.’”

In her book she writes:

“The collapse of Communism destroyed the faceless enemy upon which our national identity had been based, and had an enormous, largely unacknowledged impact upon the nation’s sense of itself. The issue of ‘who is American’ became more and more unclear. It used to be that Americans defined themselves as not-Communists. But once Communists no longer posed a threat, the drive to figure out the meaning of America became even more urgent. Communism was no longer a threat. What would replace the ‘other’ against which American identity was defined? ‘A symbolically contrived sense of local similarity,’ writes Richard Jenkins, is sometimes ‘the only available defense.’”

In Cottage Grove, Stein observed the ways that suddenly people were so skeptical of their neighbors. People they once trusted, or that they hadn’t thought twice about, were re-examined as potential interlopers once the OCA came to town. Stein writes:

“…Individuals make countless decisions about who is a friend and who is an enemy, about who should be included in a particular community and who should not. People do things because they wish to protect the image of who they are in relation to the group of which they believe they are a part. We conceptualize the world into those who deserve inclusion and those who do not. Boundaries mark the social territories of human relations, signaling who ought to be admitted and who excluded. The desire to root out others in order to consolidate a sense of self seems universal. How do human beings perceive one another as belonging to the same group while at the same time rejecting human beings whom they perceive as belonging to another group? Why must we affirm ourselves by excluding others?”

But people in Cottage Grove put up resistance to the OCA — and that resistance originated, at least in part, in the local bookstore.

When we spoke on the phone, I asked Stein if she had also encountered the same kind of feedback I had: that reading work about the far-right is too difficult for people to engage with. She raised her eyebrows and smiled.

“Well, knowledge is power,” she said. “If we don't have an understanding of what is going on around us, how things have changed, what things are possible, how can we possibly engage as social actors?”

Literacy is a form of resistance. And that’s why things like books, or the work of journalists, are seen as such a threat in the eyes of the far-right. They also don’t want you to read — but for different reasons.

“The right doesn't want those ideas to circulate in public. They don't want people to be empowered. They don't want people to be able to make choices,” she told me.

I wanted to get Stein’s opinion of Socolaw’s quote — the one I pasted up at the top of this newsletter — because it seemed so astute, but also so absolutely contrary to pieces of reporting that I have done. The far-right is not the fringe anymore. It’s mainstream now. I read it aloud to her.

“People were convinced that Trump was an agent of change and that by voting for him, he would shake things up. I don't think most people fully understand the extent to which he is going to shake things up in ways that are gonna make their lives more difficult,” she reflected. “So he was the agent of change, and the Democrats were the agents of status quo. And the Democrats did not make a strong enough case to the public for being agents of change and equality.”

Her book, more than two decades later, is perhaps more relevant than ever. And now she is watching all the ways authoritarian mindsets could creep in around her. That, she said, is something we can all need to be watching out for.

“We have to be very mindful of the ways in which our lives are going to be changing. We have to be very mindful of the slow accumulation of different kinds of authoritarian patterns that might seep in,” she said.

She points to Snyder — to the quote I told you about up above. That willingness to obey in advance is called “anticipatory obedience.”

“I worry,” Stein said, “that people are going to cave too easily.”

Highly recommended you read Jeff Sharlet’s The Undertow: Scenes from a Slow Civil War, which includes an essay about Babbitt.

Throughout the book, Stein refers to Cottage Grove as “Timbertown, Oregon” and the people in the book, with the exception of OCA’s Lon Mabon, are all given pseudonyms. It was later revealed that the town was Cottage Grove.

For the record, these local efforts were struck down by the Oregon Supreme Court.

Oh, Leah, I'm so sorry about Joe's accident, his being laid off, and the loss of your dog! 😢💔 Such awful stuff in the pit of awfulness that is now. Thank you for your eloquent words, and for doing what you do, despite the horrific mess we're all in. If it's a tiny bit of comfort, we need you. ❤️

We are all Shady characters in a sad country song right now. I'm so sorry about your dog, what a heartbreak. Heal well and know we are here, Thank you for the words, grateful for the read. I remember that asshole Mabon, what a stain on Oregon, but it didn't make me want to leave. "She flies by her own wings" or something like that. Goodnight