In my 20s, I spent many a night under the green and purple twinkle lights strung up around a dim bar called The Swamp, which was located under a bridge overpass in a part of Spokane where you wouldn’t think a bar would be. The Swamp was not for everyone. It was gritty and a little gross, and so, of course, I loved it.

The Swamp was known as a former hang-out of the film director David Lynch — a story that I am fairly certain is not true. But you and I both know that it doesn’t matter if stories are actually true if people want them to be. People wanted this one to be true, and so it was true to us. The Swamp seemed like a set from a Lynch film, and, to be honest, Spokane has always struck me as the type of place where one might be walking down a sidewalk, see an ear lying there1, and you would simply continue on your way. So there was our story. That barstool? Lynch used to sit there. (Why pay any mind to the fact that Lynch lived in Spokane from age 2 to 7?)

Lynch, a film director I admired immensely and whose perspectives on art and writing I have soaked up like a sponge, died today. He was 78.

Last year, Lynch issued a cheery announcement to let the world know that many years of smoking meant he now had emphysema. It seemed clear that our days sharing this Earth with David Lynch were now numbered, but he didn’t want anyone to be sad:

I recall the ads for Twin Peaks playing on TV when I was a kid, and I first encountered David Lynch as a moody teenager when I purchased the Lost Highway soundtrack at Tower Records (it would be a decade later that I would actually see the film). Who was this famous director who was putting my favorite bands, Nine Inch Nails and Smashing Pumpkins, on a movie soundtrack? He must be cool.

My love for all things Lynchian developed in earnest as an adult, as I committed myself to being a working artist in whatever way was available to me. I could not relate to the people who grew up in the Northwest, like I did, but made their names outside the region. Lynch left, but he was clear that growing up in the Northwest — in Missoula, and Boise, and Sandpoint, and Spokane — impacted his entire view of the world. It was not a place that he escaped from or that he rejected. He was one of us, and here he was making high art.

In the great book, Lynch on Lynch, he shared idyllic early childhood memories that could have been from his time as a young child growing up on Spokane’s South Hill:

My childhood was elegant homes, tree-lined streets, the milkman, building backyard forts, droning airplanes, blue skies, picket fences, green grass, cherry trees. Middle America as it’s supposed to be. But on the cherry tree there’s this pitch oozing out — some black, some yellow, and millions of red ants crawling all over it. I discovered if one looks a little closer at this beautiful world, there are always red ants underneath.

Lynch was a study in contrasts: a man known for the darkness of his work and, yet, for a demeanor — at least in public — that was completely the opposite. Sunny, even. This is a theme grappled with throughout Lynch on Lynch.

From the book’s editor, Chris Rodley:

Lynch not only draws from his own inner life, he has the uncanny ability to empathize with the experiences of others, whether they be male or female, young or old. He makes them his own. There is, therefore, little contradiction between Lynch’s professed happy, ‘normal’ childhood and the often tormented, extraordinary lives of his characters. Lynch’s resistance to those readings of his movies that beg autobiographical connections finds its basis here, as well as in the reductive banality of such an approach — which, in attempting to understand Eraserhead, for instance, finds it more convenient to see the workings of autobiography than of imagination and empathy.

This was mind-blowing for me to read, and continues to be, because I, too, am a person who had a happy childhood with a loving family, but prefer to steep my work in the darker aspects of humanity. Lynch made me feel okay about that — that the things you create don’t have to be an extended metaphor for your own life; you can simply be interested in exploring and documenting the human experience through your work, and in doing so, convening with others.

Of course, Lynch’s most Northwest work is Twin Peaks — the television show set in a fictional town in the Pacific Northwest. It was shot primarily in Snoqualmie, Washington. Lynch’s childhood was spent in the arid Northwest — the channeled scablands of Eastern Washington, Idaho and Montana. With Twin Peaks, he fell in love with the wetter, mossier part of the region: the place of sawmill towns, of machines churning up ancient trees, of logs piled on trucks, of diners and big waterfalls and wet boots.

Sometimes I try to think about what Twin Peaks would be if Lynch made it today. Much would be the same: the timber industry still looms larger in Washington and Oregon than any other states, the one-diner towns are still here. Every rural community, though, seems to have a weed store today, so it seems like a modern Twin Peaks would need a budtender character, or at least Dr. Jacoby would be smoking blunts in broad daylight2. But otherwise, in our modern, wildly-expensive West, Twin Peaks must seem so strange to people seeing it for the first time.

In the show, owls are the sentries of the Black Lodge, carriers of a dark power. “The owls are not what they seem,” said the greatest character ever, the Log Lady. Weirdly enough, Lynch created Twin Peaks just before tensions over owls broke the brains of Northwesterners during the Timber Wars. It was a time when sides were taken over the fate of the spotted owl, a threatened species that makes its home in the old growth forests here. Now a thirty-year-old debate, this conversation still comes up in my work all the time. People are still very angry about environmental protections, about lost jobs, about being forced to change. In the eyes of some Northwesterners, real-life owls brought them darkness.

I see those owls as a symbol of forced change. Forced change is something we’re all reckoning with in the west. Look to the ways artificial intelligence is taking over media in the west, and so many other industries. Look to Los Angeles, burning, forever changed. Look to the ways timber is worn like a cultural identity. We’re all being forced to change, and it freaks us out. We brace ourselves against the waves we know are coming, but for each person, the shield we put up to protect ourselves is different.

“Many times during the day we plan for the future, and many times in the day we think of the past,” Lynch said. Everything is always tempting us to look forward, or look back.

“We’re listening to retro radio, and watching retro TV. There are all kinds of opportunities to re-live the past and there are new things coming up every second,” he said. “There is some kind of present, but the present is the most elusive because it’s going real fast.”

There are many things that stick with me about Lynch’s work — few of them cohesive. I remember the strange dumpster scene in Mulholland Drive, his oozing Baron Harkonen in Dune, Audrey Horne dancing. The lady and her log. And, of course, the man from another place. Each were moments that struck me as deeply present — scenes I couldn’t do much more with in the moment than revel in their unique strangeness.

I think that would be fine with David Lynch, that I’m left with more of an feeling of those moments than a plot line. His works felt like a dream: Northwest gothic impressionism that feels deeply true to me, someone who has this mossy place in my bones.

Today, where I live, it is a foggy, frigid day. The mist never blew off, and I can’t even see my neighbor’s house out the window. A few minutes ago, I stepped out into the yard, and it smelled like trees. It’s the smell I always notice when I come back after any time away. It’s a very Twin Peaks day, a very Northwest day, a terribly-beautiful crappy day that I’m certain would make David Lynch smile.

A few notes:

You guys, I just spent the last week reading into a microphone for the audio version of Blazing Eye Sees All, which comes out in a little less than two months. By the end of the week, I never wanted to hear my own voice again! But, on a more positive note, it made me so freaking excited for this book to be out in the world, and in your hands. You can preorder the hardcover now, but also the audio book!

I learned a lot during my last book tour about how (a) book tours are paid for by authors unless you are famous, and (b) they are expensive. Nonetheless, I want to throw it out there that if you are interested in organizing a reading at a store or venue in your town, please let me know! I also do public speaking on the topics of my reporting, so if that’s of interest, drop me a line.

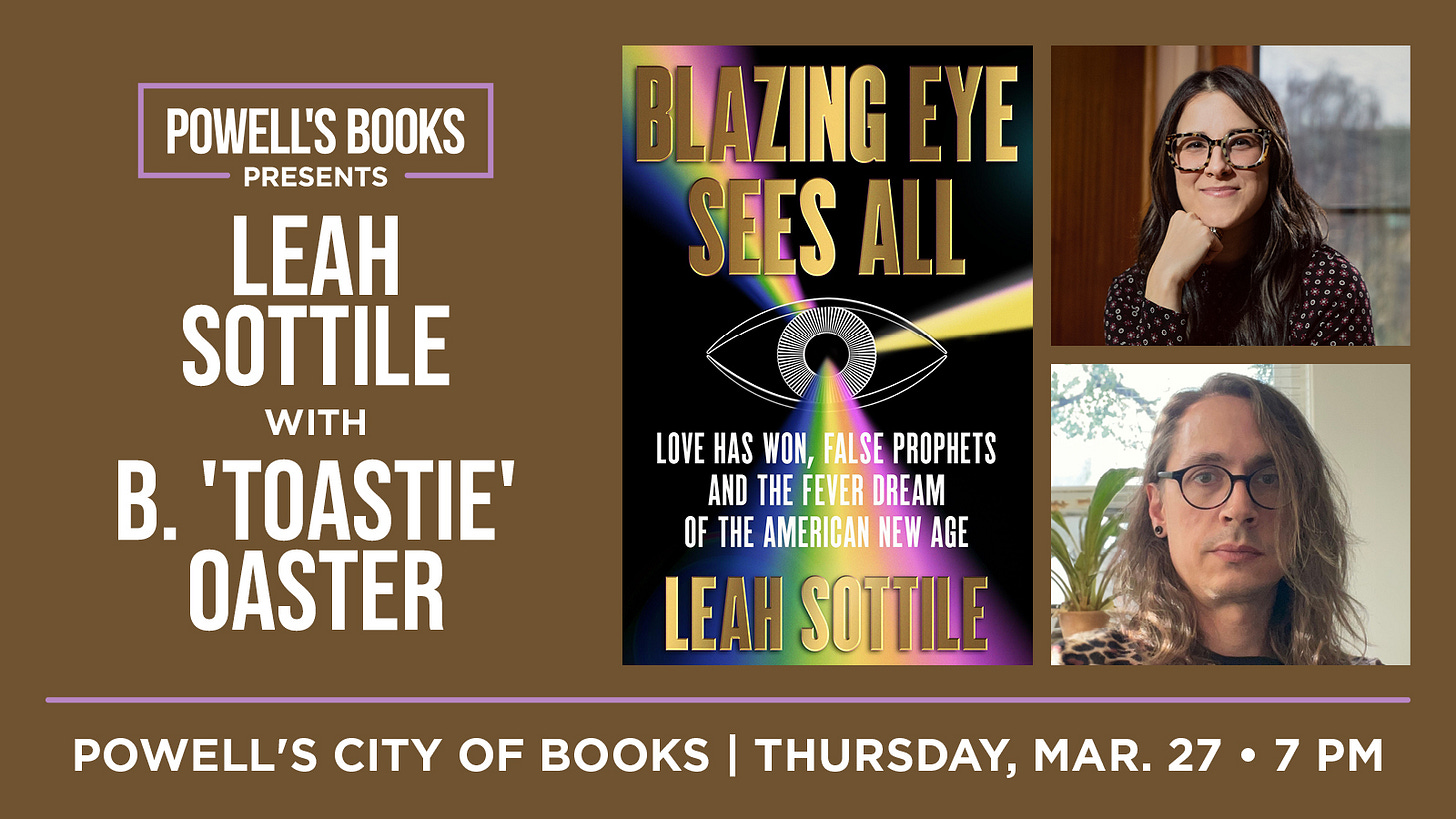

All this said: I will be releasing the book at Powell’s City of Books on Thursday, March 27 at 7 pm, where I will be in conversation with my lovely friend, B. Toastie Oaster, of High Country News. I will announce other dates soon!

To be clear, this is just my perception; Lynch said in Lynch on Lynch that the idea of finding an ear, which is an early plot point in the 1986 film Blue Velvet, was something he envisioned finding in a field in Boise, Idaho.

This is not my invitation to reboot Twin Peaks, like everything else in Hollywood, but dear god, if someone does, please call me.

I know the rest of your post is more intriguing, but this part struck me: "The Swamp was not for everyone. It was gritty and a little gross, and so, of course, I loved it." Oh, god. I love that attitude of yours, Leah, and can relate to it. Many years ago, my band and I played six nights a week in a Seattle dive called El Caballero Club. It was a seedy, awful place. There were so many fights that despite a law on the books at the time that a cop walking his beat had to be able to see through the windows from one end of the bar to the other, they gave the club a papal dispensation and allowed them to board the windows up, and simply install a porthole on the door. Why? Because so many people had gotten thrown through the windows, the owner pleaded with the authorities and was blessed. I shouldn't have, but I loved that godawful place. It provided an education I did not get growing up in the suburbs. Oh, the stories...

I was a 19 year old when Twin Peaks hit my TV and boy, did you bring back some memories. I remember the anticipation of having to wait a week for each new episode with my mom, and all the quotable quotes ("My log does not judge!!). I think I need to rewatch the series as it has been far too long, and while I'm at it, find some of the early X-Files episodes...

btw, I just put in a pre-order for your book at my local independent book store, here in northern British Columbia! I hope the Conspirituality gang have you on their podcast at some point. :)