60. Good Talk #12: Caroline Fraser

"The similarity between [smelting companies'] behavior and the behavior of the serial killers is really so inescapable."

Summer is the greatest time for reading, and as I have made abundantly clear to longtime subscribers of this newsletter, I am a capital-N nerd about books. My life is a never-ending process of clearing other things off my plate so I can have unrestricted reading time. My “to read” shelf has expanded to an entire bookshelf with an overflow pile of books stacked on top. And lately, I’ve been aiming to take breaks throughout the day to sit in my yard with a book for 15 minutes at a time, instead of scrolling through my phone.

Since I’m not a librarian (would love to be) and don’t have a job in a bookstore (if you’re hiring, reach out) I discovered I could become a Bookshop affiliate. I always think about how fun it would be to be curate the end-cap displays at Powell’s — and this is basically my version of that. If you buy books from the link below, I get 10 percent of each sale. I’m not trying to become an influencer here, but hey, being a book influencer sounds like the best kind of influencer?

I’ve created a list called “How We Got Here” which includes truly amazing books on political extremism, environmental issues and violence in America. Not happy books, per se, but all books I was actually very happy I read. (Yes, I have put my own books on this list, I got bills to pay.) I learned a ton from Seyward Darby’s Sisters in Hate, which looks at female white nationalists. Dave Cullen’s Columbine sat on my shelf for years because, honestly, who wants to read about mass shootings? But when I read it, I was floored by what I learned — and unlearned — about that horrible incident.

My list “Damn Fine Books by Authors in the American West” will be an ever-expanding list because I read a lot of books from authors in my region. My most recent reads there are Omar El Akkad’s One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This — a truly amazing work called his “breakup letter with the West” — and Keith Rosson’s addictive zombie books Fever House and The Devil By Name. Both are Oregon authors.

“Bigtime Faves” includes some of my all-time greatest hits books. I read Jess Walter’s new book So Far Gone over the weekend — a wonderful summer read I’ve included on that list. And everyone who knows me knows I won’t shut up about Long Island Compromise by Taffy Brodesser-Akner.

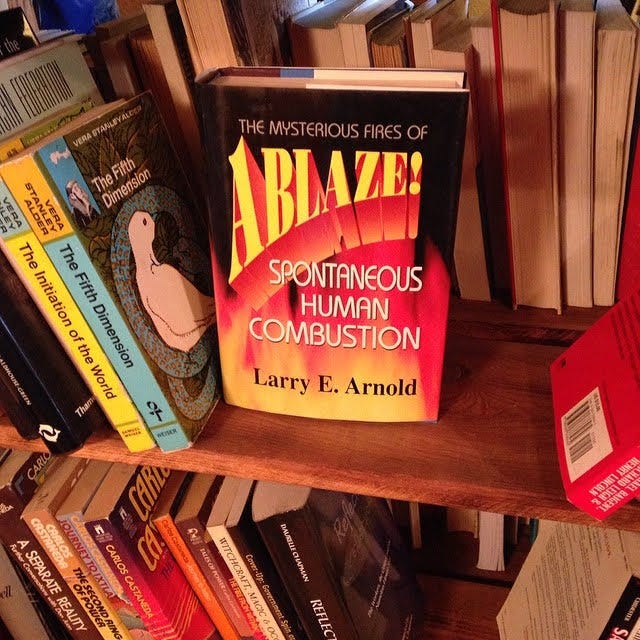

And then there’s “Crime Books With Substance.” I don’t really think of myself as a big true crime person, despite having authored two books shelved in that section. But these are the books from that genre that grabbed me, took hold and wouldn’t let go — Jack Olsen’s legendary book Give a Boy a Gun, John Vaillant’s environmental page-turner The Golden Spruce (Fire Weather, a Vaillant masterpiece, is on the How We Got here list, FYI).

Which leads me to today’s newsletter — the latest in my Good Talk series, where I interview people who inspire me. Last week I had the great pleasure to meet Caroline Fraser, journalist and author of the very new book Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers, and ask her questions in front of an audience at Powell’s.

Fraser’s book is about the Pacific Northwest’s serial killer problem. We’re talking Ted Bundy, Gary Ridgeway, Robert Yates1, Israel Keyes. Those are just the guys you’ve heard of. This is so much more than a serial killer book though. It’s a book about the very air we breathe in the Northwest. It’s about Tacoma and Mercer Island, Spokane, Kellogg, Lake Coeur d’Alene, Portland, Vancouver. It’s a book that will have you asking yourself who really is the biggest serial killer from this region. Is it these guys? Or is it the corporations who’ve, quite literally, gotten away with murder? The interview with her is below.

As always, if you like what I’m doing with this newsletter, or something I’ve written, consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber. (Details of where that money goes in last month’s dispatch.)

Leah Sottile:

Welcome to Portland — I'm very excited to talk about Murderland. As I told Caroline when we were waiting to come up here, I read this entire book aloud to my husband. It is so good. I couldn't — we couldn't — put it down. This book is a masterpiece about serial killers, the culture of the Northwest, violence, land, the air we breathe, and also you. Talk about where this book started for you, but also how you went from writing about Laura Ingalls Wilder to Ted Bundy. I am very curious about that connection.

Caroline Fraser:

They're really very similar [laughs]. Although I will point out that Prairie Fires does begin with a higher body count than Murderland because it covers the so-called massacre in which like 600 white settlers get murdered in the first 20 pages of the book. So it started off on a little bit of a down note. This book I took kind of a sharp left turn into ecological history and environmental history. In Prairie Fires, it was the whole white settlement of the West and what a disaster that was in so many ways. [With Murderland], on the cover you can see there's a picture of Ted Bundy with his face kind of superimposed on an industrial landscape, which is in Tacoma — the old Asarco smelter in Tacoma. And so that really, I think, is the connective tissue between the two. This didn't feel like it was completely out of left field entirely to me, but I can see how people might think that way.

LS:

What did your research and writing process look like? Did you know when you went in that you would be writing just as much about corporations as killers? And we can kind of talk about that definition of a killer here too?

CF:

No, the whole thing kind of evolved organically in a way, because I started by writing some of the personal memoir pieces. There’s a thing about the guy who lived down the street from me and blew up his house when I was eight. And that always kind of stuck with me.

So I started writing about some of these things and thinking about what a violent time the 1970s was. The news was constantly full of murders and bombings and assassinations and protests, so we were being told that that was unusual. But it felt kind of normalized in a way while you were living through it. So I think that was sort of what started it off, was thinking about how violent a time it was, and also this whole question of why are there so many serial killers in the Northwest?

That had been something I was always curious about — like, is that a real thing? Is it just an urban myth? Is it something that can actually be investigated? And so I started down that trail and then somehow happened across this piece about the smelter, which I had never really understood what that was. I mean, I knew there was all this industrial waste in Tacoma. I mean, everybody who's ever been there, back in the day, knew the aroma of Tacoma. It smelled very, very bad. But I don't think I understood the first thing about what that was coming from. The smell was mainly, I think, from the pulp mill. But there were more than fifty plants and refineries down there.

But when I discovered that there was a real arsenic problem on Vashon Island through a real estate ad, that was the kind of thing that I started looking at that, and the arsenic pollution, which came from the ASARCO smelter — the American Smelting and Refining Company. And lead. And I started to wonder, ‘well, could any of this stuff have had any effect on the people? Knowing that [Ted] Bundy grew up in Tacoma, that Gary Ridgeway grew up just north of Tacoma by Sea Tac. And then somehow this other little tidbit came my way about Charles Manson — that he had spent five years incarcerated on McNeil Island at the same time that those other two were growing up there. McNeil Island is very close to Tacoma as well. I learned about the whole smelter plume and what that had done to the Pacific Northwest.

LS:

And just to be clear, this book doesn't stop at Bundy, Ridgeway, Manson. It goes into Israel Keyes, which was a very surprising thing for me to see, and Robert Yates over in Eastern Washington. It is extensive in the way it covers serial killers, but also their victims. Every victim in this book, no matter who they are or what they were killed by, gets a lot of space. And I wanted to talk to you about this choice.

CF:

Yeah, I mean, one of the things that I hoped to do by explaining what these guys did in some detail, but also who they were doing it to, was to kind of reorganize the true crime tropes. I think a lot of true crime ends up sort of glamorizing the killer. They're the star of the show. But a lot of these guys, particularly Bundy, come off as almost like these evil geniuses, you know? They’re painted as these kind of Hannibal Lecter-type figures who can escape detection. But the thing about lead and lead exposure is that it really sort of reorganizes your brain if you are exposed to it as a kid. All the things about controlling your behavior and your impulses are affected. Kids who have been exposed seriously to lead can become much more aggressive and much more violent. And so, in describing what, say, Bundy or some of these other guys did in a matter-of-fact kind of way really corrects the impression that these guys were geniuses. Because they were not geniuses. They were cunning in many ways, but they certainly were not some incredible level of criminal capacity. And in fact, almost all of these guys were pre-DNA, and that's mainly the reason why most of them didn't get caught. And also just the incompetence of the police. But to your point, yeah, I mean, I think that the, the women who got murdered in many cases were far more interesting and valuable as people. And so it just seemed natural to kind of describe who they were and what was lost.

LS:

It's really effective. And I found myself getting really nervous every time a new person was introduced into the plot, where I was like, ‘is this person going to get killed or are they going to get away?’ But I felt like that was really appropriate — like perhaps I should always be nervous reading a book about murder and murderers. But there are shows out there about picking your favorite murderer. So I’d like to talk to you about the ethics around true crime. Did you worry that this book would be shelved as true crime? What were your thoughts around being a part of the genre?

CF:

It actually turned into kind of a tussle with the publisher because they were really nervous about having this labeled as true crime. I didn't mind it in a way. I mean, everything you're saying about true crime is true. The origins of true crime are incredibly sleazy. It essentially began as this kind of soft-core porn for men that was sold in drug stores and was illustrated with these horrible color illustrations of women being strangled or stabbed. But the more I looked at the evolution of true crime, especially in the last 25, 30 years since Ann Rule's book about Bundy, The Stranger Beside Me. I'm talking just about books here, not about tv — which is a whole other story. But in books, I think there's been a lot of movement to make true crime, really, the history of crime and the history of crimes against women.

So I think it's evolving and I didn't mind being tagged with that, because what I wanted to do in the book was to present a kind of whole history of this topic: all the stuff that happened with serial killers and the history of violence in this period. Crime in the US went up quite sharply in the 1970s and ’80s along with the fruition of leaded gas and smelters. Those heights of the crime rate have never been exceeded since. So it went up, up, up, then it leveled off when leaded gas was removed from the market, and it abruptly fell off.

So the book is looking at that history, the period of time in which lead did its worst and had the results that it did, and then was removed. The smelters closed down. We now have far less crime than we used to have. All this stuff that you're seeing in the news now, of the Trump administration claiming that crime is at its worst, and it's just a horror show out there. That's all complete misinformation. It’s really lies.

LS:

As I read this, I started to wonder or pick up an argument you were making, that the serial killers maybe we've all been focused on are not actually the biggest serial killers. Talk about this environmental research that you did and where you landed on the effects that these, these companies, these corporations, multinational corporations have had on people's health.

CF:

I think it's inescapable that when you look at the behavior of, say, ASARCO, which was owned by the Guggenheim family, and some of these other entities, like the company that was running the smelter in Kellogg, Idaho — Bunker Hill. The similarity between their behavior and the behavior of the serial killers is really so inescapable that it's almost funny. You can't even believe what these guys did. In the Bunker Hill case, they lost control of their filtration system in 1973 when a fire broke out and destroyed a lot of the filters that were keeping lead — or some of the lead — out of the environment. They just decided because the price of lead was so high, they were just going to keep running their lead smelter full blast for months and months. And they did this back of the napkin calculation of how much they would have to pay for killing or crippling all these kids in the town of Kellogg. And they decided, ‘well, that's worth it because it's going to cost us more to shut the plant down.’

They were murderers. They were liars and murderers. And it's the lying that I'm really fascinated by, because it's so calculated and furtive and they just can't control themselves.

LS:

As someone who's spent an inordinate amount of time swimming in Lake Coeur d'Alene. That's not a thing I think I'll do again after reading your book. I was surprised to learn how many of these communities, specifically like Kellogg and Wallace and in North Idaho, the people there knew about a lot of the pollution that was falling on them and their children, but chose to stay. I thought that was an interesting thing to point out about the culture.

CF:

I think it's an illustration of the desperation of a lot of these towns that they were the only jobs. And so people were being forced to choose between being destitute and not having a job, or having to go somewhere else to find a job and surviving. And they took a risk. A lot of the guys who worked in the Tacoma smelter, those jobs were just the most horrible. Dangerous. You're working with these giant vats of molten metal, moving them from place to place and pouring molten metal. Guys got their eyes put out by chunks of hot metal flying through the air. Just really hellacious circumstances. This is why none of these places can reopen now, because the OSHA regulations and the EPA.

LS:

Talk about how all of this squared up with the commonly held perception that places like Washington and Oregon are extremely green states, very friendly to the environment. I found myself wondering if I had been subjected to some kind of propaganda growing up here.

CF:

Well there's what you see and what you can't see. Growing up in Puget Sound, it's so beautiful, and all the recreation, the mountain climbing, the skiing, the water sports, the sailing, all of that — it's deceptive. It's like swimming in Lake Coeur d'Alene, which I have swam there myself. It's a beautiful mountain lake, and you look at it and you can't tell that there's anything wrong with it. You can't tell that it's full of lead and a lot of other stuff that is at the bottom. And what could happen with Lake Coeur d’Alene is that if the water continues to be oxygenated by all the septic systems and all the other stuff that's being built out there, that could agitate and change the chemical composition. Lead could start entering the water column and rising up and really changing what that looks like and smells like. I hope that doesn't happen, but that's the risk that they're running.

LS:

The EPA in March touted the biggest deregulation of the Clean Air Act since it was sponsored. Now that you've written this book, how you hear that news?

CF:

Well, it's dismal. I'm not suggesting that we're going to go back to the state of the things that I was describing in this book, because that's very unlikely. Nobody's going to start selling leaded gas anymore. Nobody's going to reopen the smelters for the reasons that I just described. But there are so many other ways in which we're putting these chemicals and heavy metals into the environment. I think almost every day there are new discoveries about lead in schools, in crops, and applesauce, and baby food, and toothpaste. There's a lot of lead out there that has to be contended with. We have to do something about it. And then there's also all the news about all the particulate pollution. Lead causes heart disease, it doesn't just cause you to be crazy and violent. It can cause ALS. And all this particulate pollution — some of which includes lead and cadmium, and carbon monoxide and, you know, a whole suite of different things — those are killers too. And so the fact that they're just not going to regulate or, or cut regulations, on these plants is really bad news.

LS:

So much of this book is also about you and growing up on Mercer Island. There are so many fantastic essays in this book. There's mentions of Twin Peaks and David Lynch and all these things that I love. But talk about this essay component a little bit more. Obviously you talked about how a house blew up down the street — that's a notable childhood event to write about. But there's a lot more essay here about your family.

CF:

I sort of wanted to recreate what it was like in the 1970s. Domestically, it was a very different environment and there were a lot of different expectations and there was a lot of, of violence in the home. I think at that time there was domestic violence, there was corporal punishment in schools. All kinds of stuff was subtly different. And there was a real male prerogative at work. And I think that's why I brought in some of the descriptions of my father who was kind of a scary guy. It was not to say that he was a serial killer, but just to show that there's kind of a range of behavior — that even things that seem fairly mild or not that malevolent can be threatening in a home environment or at school.

I sort of wanted to give a sense of what it was like to grow up then for girls to hear about all the kind of news of the stuff that was happening about. With Bundy, I do remember the weekend of Lake Sammamish in July of 1974. I was 13 years old. And just hearing about these women who had disappeared and just thinking, ‘what does that mean? Where are they? What happened to them?’ And not even being able to conceptualize what that was all about.

[Note from Leah — I don’t usually include audience questions in these Q&As, but I wanted to include one here because Caroline’s answer was great.]

Audience Member:

What was the most surprising thing you learned in the process of writing this book?

CF:

Well, I was pretty surprised that that entire generations of people in the Northwest were deliberately poisoned with arsenic and lead by the decision of this corporate, you know, actor. I mean, you go to the Guggenheim Museum now, and you could talk to a hundred people who are in that museum and ask them, ‘how did the Guggenheim's make their money?’ And I bet nobody would know the answer to that, but that's how they made their money. And I have to say, it was something that made me really, really angry to learn about that. So if that counts as surprising, I think, I think that was probably the most surprising thing to me.

The writer Alayna Becker wrote an incredible essay for Pacifica Literary Review called “Bad Trick List” a few years back on growing up in the long shadow of Robert Yates on Spokane’s South Hill.

I read The Golden Spruce many years ago, and your mention of it reminded me that I was working as a summer lab assistant at UBC in the tree physiology lab when Hadwin killed it with his chainsaw, and all the researchers were running around trying to figure out how to clone the damn thing. It was eventually grafted successfully in Ontario, I believe. I think there was an old cutting from the original tree from the 1970s that they managed to turn into a seedling to replant next to the stump. I really need to go back to Haida Gwaii to check it out - it's a beautiful place. I've been twice now, for both work and pleasure.

Also, a book about female white nationalists?? This is something I need to look for. I just ordered Jane Borden's book "Cults Like Us" which looks at the link between the Puritanical roots of the U.S. and the things that make your country so weird. :)

I don't know if you've read this book about a supposed PNW serial killer, but it's probably your kind of thing: https://uwapress.uw.edu/book/9780295751207/the-port-of-missing-men/