If you’ve ever driven north up Interstate 5 through Washington State, you’ve seen the Uncle Sam billboard in Chehalis. Locals in Lewis County call it “the Hamilton Sign.” It’s named for Alfred Hamilton, the conspiratorial turkey farmer who put the billboard up in the 1960s1 and used it to blast his piggish views into drivers’ eyeballs ever since.

Hamilton, a proud John Birch Society2 member who died in 2004, was an OG troll — someone who really seemed to get off on riling people up. People use Twitter now; he used a billboard with a dopey-looking Uncle Sam.

Trolling the general driving public wasn’t always easy. Hamilton fought off numerous court challenges over the decades. In 1975, the state of Washington sued him, arguing the sign should be removed because the messages violated the Scenic Vista Act and were a public nuisance. Around that time, the Uncle Sam sign featured messages like “Women are meant to be cherished, not liberated” and “Non-communist straw for sale.” The state lost.

In 1979, it looked like Hamilton’s sign would come down after a Washington state Supreme Court judge ruled that three John Birch Society signs on the other side of the state, in Stevens County, had violated the law. Still didn’t work; Hamilton’s sign remained.

“He was a fighter,” his daughter told The Chronicle when he died. “He loved a fight.”

Last year, in June 2024, I wrote a story for High Country News all about the persistent far-right extremism around the area of the sign. The Northwest, as you may know, has a big reputation of being a bastion of liberalism, and yet it also has a big reputation for nurturing some of America’s most hardcore extremists3. So what gives? What does it say about the region if the Hamilton Sign could exist in a place so supposedly progressive?

In Lewis County in particular, answering that question goes back to 1919, to a bloody incident that played out in the streets of Centralia. For the purposes of this newsletter, here’s a recap from the story of relevant information:

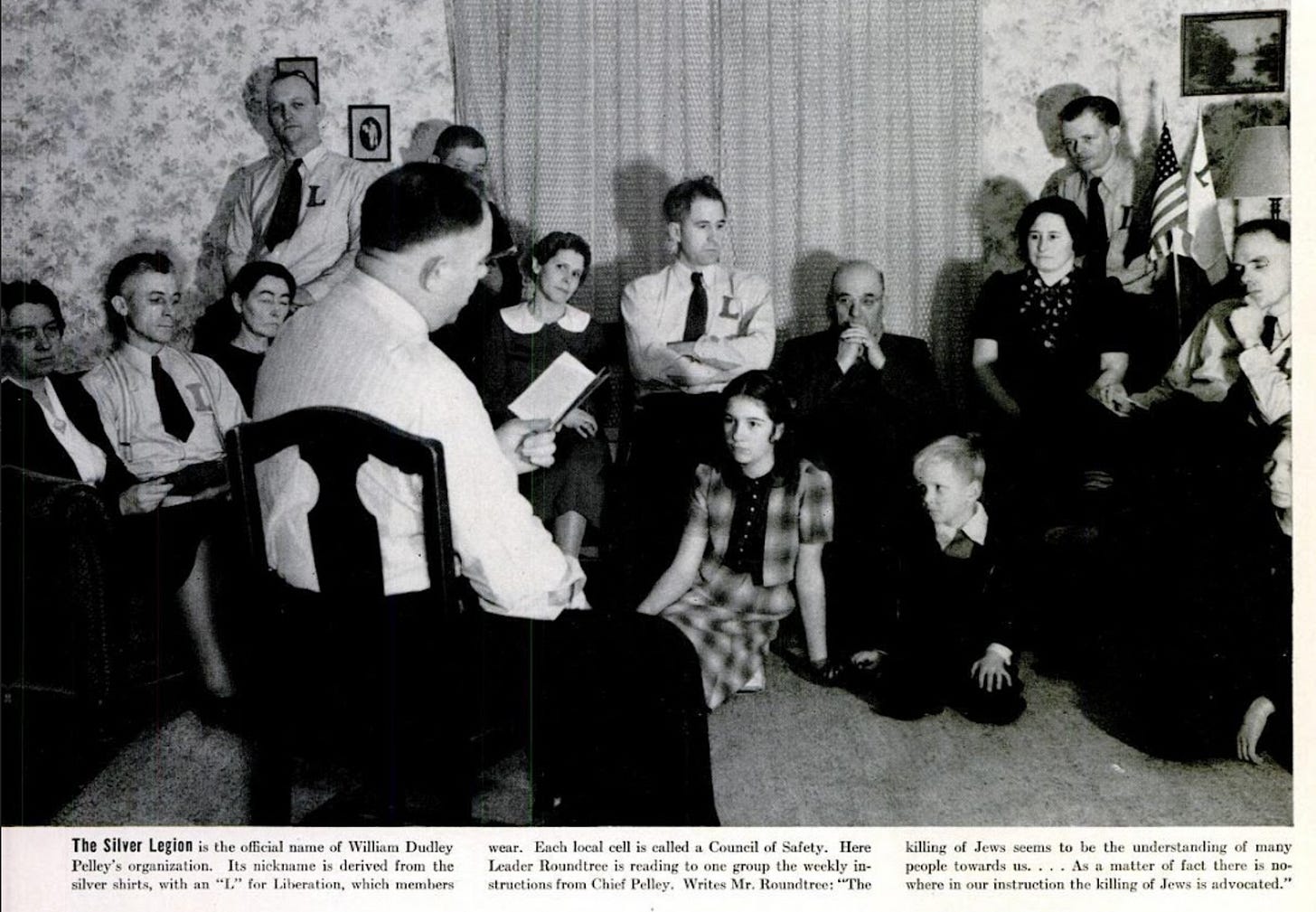

In March 1939, LIFE Magazine published an article called “Fascism in America,” which highlighted the Chehalis Silver Shirts in a large black-and-white photo. Afterward, Robert Cantwell, a novelist who grew up in Lewis County, wrote to LIFE. “Fascism cannot be explained only in terms of fanaticism,” he said, “the history of the places where it gains a lodging must also be taken into account.”

Cantwell wrote that the November 1919 incident “stunted” Chehalis and Centralia’s political growth. “Fear of radicalism, hatred and fear of social changes, distrust of the working class” have plagued it ever since. The ideologies morphed and shifted with each decade’s culture wars. “Communism” at first denoted anti-capitalist Wobblies, but by the 1930s, people like Pelley and the Silver Shirts had expanded the term to encompass Jews. With each decade, more groups of people were included. Communists were outsiders — and outsiders were enemies.

In the 1960s, the John Birch Society — a conspiratorial far-right organization that stoked fears over Communism — capitalized on this. Local supporter Alfred Hamilton put a billboard just opposite his Chehalis area turkey farm to shout conspiracies at passing drivers on Interstate 5.

A version of the sign remains. Known as “the Hamilton sign,” it features a cartoonish Uncle Sam with a continuously rotating message. “BE THANKFUL YOU LIVE IN AMERICA,” Uncle Sam said in the 1970s. “GUN CONTROL IS A STEP TOWARD ‘PEOPLE CONTROL.’”

In every era, Hamilton’s sign reflected the shifting views of conservatives, hinting at which “outsiders” were most to be feared.

In the 1980s and ’90s, it was the LGBTQ community. The sign branded a nearby college as “HOME OF ENVIRONMENTAL TERRORISTS AND HOMOS,” and said the then-governor’s order banning discrimination against gay and lesbian state workers “SEEMS A LITTLE QUEER.”

“WHERE’S THE BIRTH CERTIFICATE?” it demanded during the Obama years.

By 2020, the sign was primed and ready for COVID conspiracies: “OH, NO! A VIRUS. QUICK – BURN THE BILL OF RIGHTS!”

My story talks about recent manifestations of hate in that area: a bunch of Nazis who showed up at the Centralia Pride festival in 2023, the vandalism of county-wide LGBTQ landmarks with black paint, the arrest of three men affiliated with Patriot Front.4

There are times American political life feels like stagnant pond water — never moving, only festering. Consequences are a mirage. Justice seems to not extend as high as the halls of power. Everything feels rotten from the inside out, and all us regular people are forced to live in the stink, doing that thing where we try to act normal, like we can’t smell anything. Every now and then, seems like the wind blows hard enough, and the stench goes away, but it can be fleeting.

Earlier this month, the wind blew. Northwesterners got some surprising good news. From The Seattle Times.

The highly contentious Uncle Sam billboard off Interstate 5 in Lewis County has a new owner: the Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation.

And yes, the tribe intends to take down the right-wing messages that have lingered on the 40-foot-by-13-foot sign for years.

The tribe closed on the 3.5-acre property hosting the billboard for $2.5 million in cash Friday morning, said Chehalis Re/Max real estate associate Israel Jimenez, who listed the site for sale on March 3. The property went up for sale when the owner’s family decided to reposition their assets, Jimenez said in March.

The property, though small, has historical significance, said Jeff Warnke, the Chehalis Tribe’s director of government and public relations.

The sale presented an opportunity for economic development right next to I-5 with good signage, but it’s also an opportunity to buy back tribal land the Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation ceded more than 150 years ago, Warnke said.

At the end of the story, Warnke added this delicious tidbit:

Warnke’s family has lived in the Chehalis area for two generations, and he remembers riding past the billboard messages since he was a kid.

“Some of it’s funny. Some of it ain’t,” he said.

The tribe has “had a good time thinking of crazy stuff we could put up there,” Warnke said, but it hasn’t landed on anything concrete.

One musing, Warnke said, was a message informing people that the property is tribal land.

It’s such a sweet little two-fer of news: the billboard that outlived its owner by 21 years will come down and the land underneath it will be back in the hands of its ancestral owners.

I’ve been thinking about this as we head into the Fourth of July, Independence Day. Uncle Sam, the caricature on that sign, is the kind of iconography I associate with this holiday — an occasion I loved as a kid, but as an adult, I’ve come to be less fond of. Fireworks start wildfires in Oregon; I think anyone who lived through the 2017 Eagle Creek fire — when a teenager hucked a firecracker into a dry ravine as his friends shot a video, and almost burned down 50,000 acres of the Columbia River Gorge — probably shares that fear. The pops and bangs scare my dogs, and sound like gunshots. And then there’s, you know, the whole project of colonialism.

Prompted by the holiday, and the death of the billboard, I did some reading and was surprised to learn Uncle Sam is actually named after a real guy. According to Natalie Elder, writing for the National Museum of American History, a well-liked Troy, New York man named Sam Wilson delivered barrels of provisions to soldiers fighting in the War of 1812. The troops called him “Uncle Sam.” His barrels were marked with the letters “U.S.,” which wasn’t common shorthand for the country at the time. Sam was ahead of his time in that regard; he meant it to stand for “United States,” but the soldiers read it as his initials: Uncle Sam.

This character Uncle Sam — the embodiment of the country as a man clad in red, white and blue clothing5 — didn’t take off until around the time of Centralia’s bloody tragedy, in 1919. (The recruiting poster above is dated to 1917.) Here was this stern, aging white man in a top hat — the chapeau of the elite — looking down the barrel of a pointing finger, saying hey, you there, get off your butt and get to the front line. He’s not quite a father-figure, but an uncle — family nonetheless.

Uncle Sam — white, aging, male, wealthy — was a recruiting tool for the military, a violent arm of our society. Call me crazy, but isn’t violence a way of dictating just how independent someone can be?

That time around World War I was an era when political leaders stoked fears that communists were lurking around every corner. In Washington and Oregon, communists were actually workers wanting rights on the job. They were loggers who didn’t want to get trench foot or be mangled by machinery while working in the less-than-humane conditions of a timber camp. They were threatened with violence.

Just like the word communism has continually been given new meaning by political leaders over the years, you can see the way independence is, too, redefined through Hamilton’s Uncle Sam. Independence is only for a few.

News that the Uncle Sam sign would come down came just two days after another bit of extremism news in the very same area: A pair of ex-military members were arrested not far north of Lewis County after being caught stealing guns, explosives and body armor from Joint Base Lewis-McCord, near Tacoma.

According to federal court records, inside the pair’s home, there were “numerous Nazi/white supremacy memorabilia, murals, and literature in every bedroom and near several stockpiles of weapons and military equipment.” There were Nazi flags on the wall. They sold tshirts that read “professional war crime committer.”

The arrests and the sign coming down felt like one step back, one step forward in the fight against extremism. A terrible dance that never progresses, only stays in the same place.

In researching the arrested men, I found a Facebook page for one of them. One of his last public posts featured a meme that read “you are confined only by the walls you build yourself.” It seemed ironic now to read it, considering the person who posted it could very likely find himself walled in by literal prison walls, if convicted.

What was the common thread here? Hamilton walled himself in, too. His sign showed off the walls he built, all the groups of people he despised. For more than fifty years, he was so proud of his walls. And now his display is gone.

The rhetoric of 1919, the rhetoric of the sign, is all around us. President Trump called the Democratic nominee for New York City mayor “a pure, true communist.” He throws this label at all kinds of people he sees as enemies. Trump, too, comes from a historically liberal place: New York. It’s easy to talk about far-right extremism like it’s the sole project of rural, conservative places; it’s much harder to wrap your head around the fact that it’s everywhere.

We know now that the Hamilton sign was up for almost 70 years because it tapped into sentiments that are so deeply held in this country. Tearing it down maybe is one way to start dismantling those sentiments. But it might also be mowing over a patch of dandelions. They’re going to come back. The key is to remember they were there and not be surprised when they do.

If you liked this essay, please consider supporting my work. I’m an independent journalist covering issues of political and religious extremism, policing and class in the Western United States through magazine stories, podcasts and books. This newsletter is for essays. Here are three ways to financially support what I do:

A paid subscription to this newsletter! Paid subscribers are literally funding independent journalism with their dollars, and I also am experimenting with the Substack “chat” feature, for paid subscribers, where so far I’ve just been nerding out about books. Come on over and ask questions.

Purchase a copy of my books: Blazing Eye Sees All came out earlier this year, and When the Moon Turns to Blood released in 2022

Shop the books in my Bookshop! It’s like a teeny bookstore curated by yours-truly, and I get to keep a small percentage of every sale.

FYI, I fact-checked this and can’t seem to find the exact date Hamilton put up his sign. One article from April 1979 in The Olympian said the sign went up “some 20 years ago,” but I could not find a record of it in the late 1950s.

A book I on my shelf refers to the John Birch Society as “one of the most cussed and discussed organizations in the United States,” and I think that’s extremely accurate.

These arrests played out as I was finishing this story. At the eleventh hour, no less. My story was due on a Friday, and on Thursday, the vandalism incident in the story occurred. What to do? Drink a shitload of coffee, drive very fast to Chehalis and catch the arraignment for the accused. Later, each was acquitted by a jury of felony hate crime charges, but were sentenced by a judge to 364 days in jail for malicious mischief. Journalism! So exhilarating and stressful.

I have included a photo of President Trump pointing and wearing red, white and blue clothing. I could draw parallels, but I think we’re all pretty clear on what I’m doing here.

Great piece, that billboard was a fixture of our summer travels to the San Juan’s, my kids were always wondering what it would say “this time”. I had heard the tribe was going to replace it with tribal facts/info on a new sign, was looking forward to that, kinda the ultimate 180.

I'm so glad someone finally wrote about this weird billboard's history. And especially glad that it's you. Leah.